The Nurture Originals, Foster Art and Keep Entertainment Safe (NO FAKES) Act has had a controversial update that now addresses gen-AI “replicas” by creating an entirely new intellectual property infrastucture. Many critics argue that it crosses into over-censorship.

The term digital replica is defined in S.4875 as “a newly-created, computer-generated, highly realistic electronic representation that is readily identifiable as the voice or visual likeness of an individual.” This is colloquially referred to as a deepfake.

In essence, this bill was created to protect us from our likeness being used without our permission. However, there is considerable debate on how this will look in practice.

Currently, intellectual property disputes on the Internet are governed largely by the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA). Under Section 512, the DMCA creates a “notice-and-takedown” system for handling copyright infringement. Platforms are granted “safe harbor” protections, meaning they are not held legally liable for user-generated content if they remove infringing content when notified. Also the user that uploaded the content onto the platform has the ability to contest it by submitting a counter-notice if they believe the takedown was in error—providing a mechanism to defend fair use.

DCMA Subpoenas

However there have already been abuses with the DMCA system as is.

For example, companies will often file DMCA takedown notices or subpoenas (under 17 U.S. Code § 512(h)) even when the content is clearly fair use.

In some cases, these subpoenas are automatically approved by a court clerk, without judicial review, and require platforms to disclose the identity of anonymous users—including whistleblowers. This is because the platform is the one receiving the subpoena, and unless the platform pushes back to protect the user, their identity will inevitably be revealed.

Copyright Filters

Another key issue is the growing use of copyright filters. These are automated systems platforms use to detect and block copyrighted content before it can be published. There is no current legislation enforcing these filters. As of now they exist as platform-created systems, implemented voluntarily by platforms to avoid DMCA lawsuits.

The issue with these filters is that they don’t understand the context of the content they are blocking.

They often block fair use, parody, educational, or transformative content simply because it shares superficial similarities with copyrighted material.

In fact in 1998 Congress rejected proactive filtering when passing the DMCA out of concern for free speech. This contrasts to the EU’s Article 17 of the Copyright Directive which does requires platforms to prevent the availability of copyrighted works, effectively mandating upload filters.

So there are two issues for me here:

- The burden being placed on the platform, which incentivizes them to block potentially legitimate content to avoid liability and in turn stifles free speech

- The lack of safeguards against known system abuses, building on a flawed system and removing checks like counter-notices and fair use assessments.

Who Carries the Burden?

I think it’s important to take a look at the actual language being used in the NO FAKES bill, rather than relying on jounralist interpretations. So here it is below.

For generative AI developers

Tools used to make deepfakes will be held liable only if (1) it was designed primarily to create deepfakes, (2) has limited commercial use outside of deepfake creation, and/or (3) it is specifically marketed for producing deepfakes. This is similar to the “Betamax clause” from the Sony v. Universal Supreme Court case in which developers are only safe if their tool has substantial lawful uses.

Betamax Clause

In the Supreme Court case of Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc. (1984) Universal Studios sued Sony for selling the Betamax VCR, claiming it enabled copyright infringement because users could record TV shows without permission. Sony argued that the VCR had substantial non-infringing uses, like time-shifting (recording a show to watch later), which is legal. The Supreme Court’s ruling established the legal principle that a manufacturer of a device cannot be held liable for infringement if the device is capable of substantial non-infringing use.

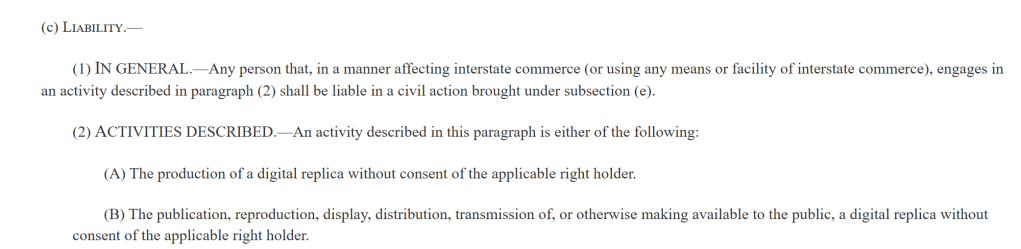

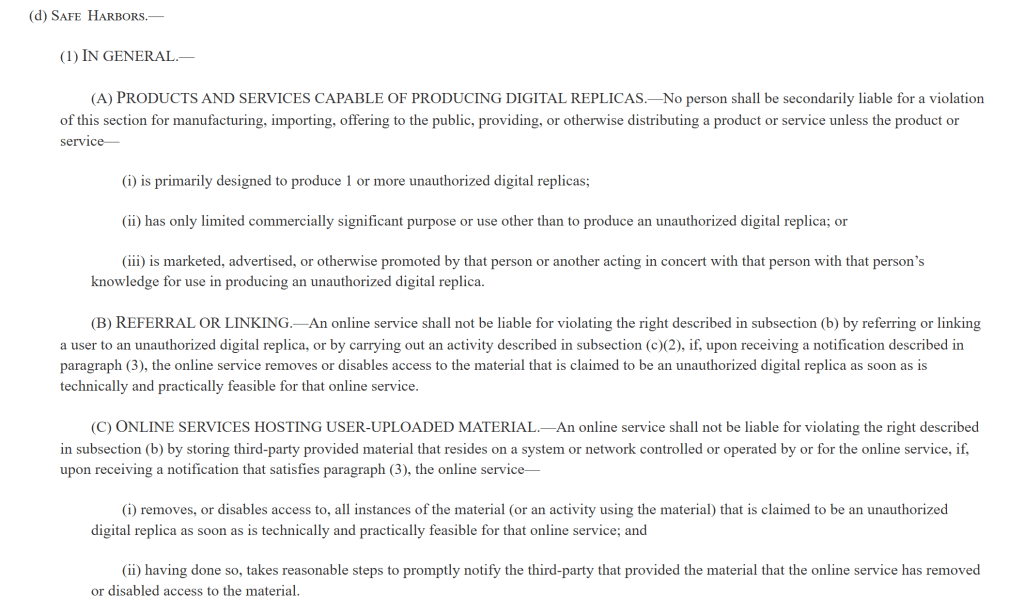

For platforms that link to deepfakes

They will be held liable if they do not remove the link as soon as technically and practically feasible after notification. Unlike the DCMA, there is no counter-notice system meaning the takedown is mandatory without any room to provide context.

For platforms with deepfake uploads

They will be held liable if they do not block all instances of the content quickly and notify the uploader afterward.

All of these elements may sound like safe harbor, but they are missing critical points that are notably present in the DCMA:

- No balance for fair use

- No way for users to defend their content

- No standard to prove that takedown requests are valid

- No disincentives for abusive notices

Take It Down

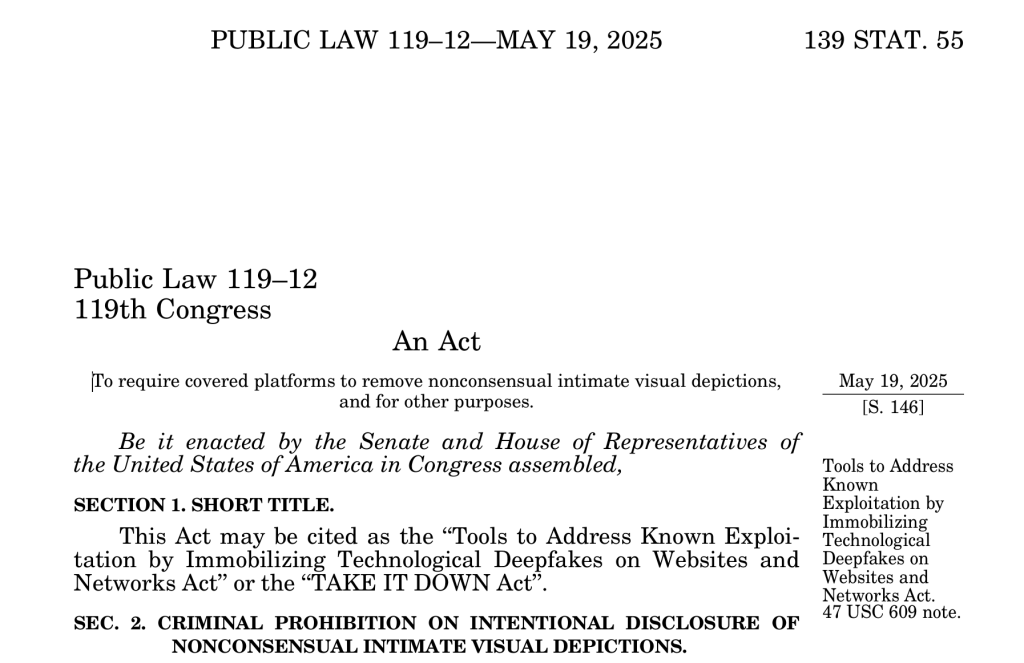

It’s clear that the NO FAKES Act appears to be following in the footsteps of another recent bill: the Take It Down Act, which Congress passed a few months ago. That law was intended to help individuals—especially minors—remove non-consensual intimate imagery from the internet.

I would like to note that during my research that I watched a YouTube video from Taylor Lorenz calling the Take It Down Act as a “free speech killer.” I found this to be an interesting take since the premise of the act was to “require covered platforms to remove nonconsensual intimate visual depictions, and for other purposes.”

As I continued to watch the video it became evidently clear that the both the host and guest had an anti-Trump political leaning which then made it difficult for me to discern how much their bias was influencing their interpretation of the legislation. I began to question whether there was a true weaponization concern or if this was another “boy who cried Trump” pile on. I believe the preservation of free speech and the avoidance of government overreach online is of the utmost importance. However I noticed some inconsistencies in this conversation that deserve a closer look—particularly in how political bias, enforcement, and censorship are being framed.

For instance, the interviewee suggests the bill will be heavily enforced when it benefits political actors like Trump, yet also says it will fail victims who need it most. If the bill really mandates takedowns in 48 hours, wouldn’t both groups be affected equally? That contradiction raises questions about whether the concern is truly about enforcement or about whose speech is prioritized.

It’s also worth noting that many of the same groups warning about censorship under this bill were supportive of platform enforcement actions in recent years. Previous iterations of censorship supported by this party included fact-checking, hate speech bans, and pandemic misinformation takedowns. If the concern now is about ‘free speech for all,’ then the inconsistency in past moderation support should raise an eyebrow.

Legislative History of Online Censorship

Section 230

To understand the significance of FOSTA-SESTA we first have to take a look at Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996 which states “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.”

This means that platforms (e.g., Twitter, YouTube, Reddit) are not legally liable for content posted by users. They’re not “publishers” the way newspapers are.

Section 230 has become a foundational law for the open web that protects platforms from being sued just because a user posted something offensive or illegal. It also allows platforms to moderate content (e.g., delete hate speech or misinformation) without being treated as the author of that content.

FOSTA-SESTA

FOSTA-SESTA is a combination of two bills:

- SESTA: Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act (Senate)

- FOSTA: Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act (House)

It was passed in 2018 with bipartisan support and ended up amending Section 230 to say that platforms can be held liable if they “Promote or facilitate prostitution or sex trafficking.”

It created an exception to Section 230 immunity, allowing federal criminal charges, civil lawsuits against platforms, and state-level prosecutions.

EARN IT Act

EARN IT Act (Eliminating Abusive and Rampant Neglect of Interactive Technologies) was a bill originally introduced in 2020 and reintroduced in 2022 and was framed as a way to fight child sexual abuse material (CSAM) online.

It would remove Section 230 immunity for platforms in cases involving CSAM. It also proposes creating a federal “commission” (mostly law enforcement) to develop best practices for content moderation. Platforms would lose their 230 protections if they fail to follow those best practices.

This puts encryption is directly in the crosshairs. For example, if a company uses end-to-end encryption, and law enforcement can’t access the data, that could be considered noncompliance. This indirectly pressures companies to weaken or backdoor encryption to retain legal protection.

Doing this steps into mass surveillance territory by forcing platforms to weaken encryption so they can scan user messages—undermining privacy and security for all users.

KOSA

The Kids Online Safety Act (KOSA) was marketed as protecting children from online harm, like:

- Radicalization

- Depression

- Eating disorders

- Cyberbullying

- Sexual exploitation

KOSA required platforms to enable filtering tools for parents and disable algorithmic content that might be “harmful.”

And because this would be enforced by state attorneys general and the FTC, it would be up to their interpretation to decide what is defined as “harmful.”

Addressing Political Leanings

What’s especially complicated about legislation like the NO FAKES Act is how its interpretation is increasingly shaped by partisan narratives. A growing number of criticisms tend to originate from one political party or ideological camp.

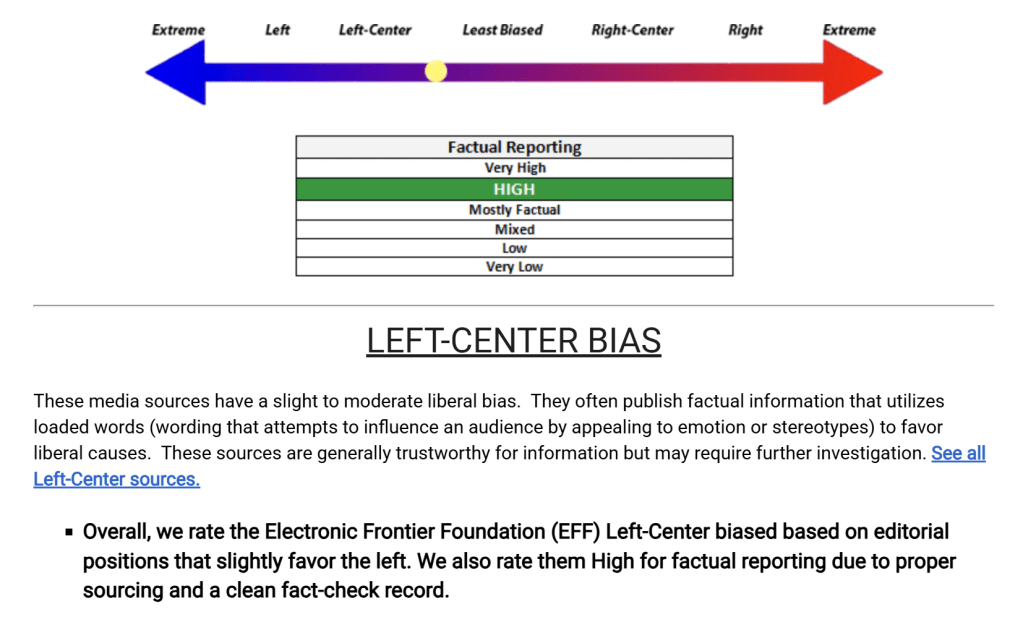

For example, the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) where I had originally picked up the article from was rated as having a left-center bias on MediaBias/FactCheck, as you can see them explain further here:

The organization publishes news and analysis with minimal bias, such as this Supreme Court Overturns Overbroad Interpretation of CFAA, Protecting Security Researchers and Everyday Users. The EFF’s Deeplinks blog delves into politics, especially as it relates to cases against the government. For example, they have provided analysis on what the Trump administration meant for the first amendment and civil rights, often with a negative tone Dangers of Trump’s Executive Order Explained. However, when reporting on Democratic President Joe Biden, they have a more favorable tone asking him to change Trump-era policies EFF’s Top Recommendations for the Biden Administration. All information reviewed is properly sourced and factual and leans left in bias.

Therefore I have to ask, is the bill really flawed or are the ones sounding the alarm bells grasping at straws?

As we’ve seen, many of the voices now warning about censorship were previously supportive of aggressive moderation in other contexts. So when these same groups criticize NO FAKES or the Take It Down Act, it’s challenging to tell whether the outrage is about principles, or about political positioning.

This ideological inconsistency muddies the waters. It doesn’t mean these laws are harmless—it means we need to evaluate the bills on their actual merits and risks, not just through partisan lenses.

Sources

Media Bias/Fact Check. (n.d.). Electronic Frontier Foundation. Retrieved June 27, 2025, from https://mediabiasfactcheck.com/electronic-frontier-foundation/

United States Congress. (2023). S.4875 — Nurture Originals, Foster Art and Keep Entertainment Safe (NO FAKES) Act [Bill text]. Congress.gov. Retrieved June 27, 2025, from https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/4875/text

United States Congress. (2025). P.L. 119‑12 — Take It Down Act. Public Law 119‑12. Congress.gov. Retrieved June 27, 2025, from https://www.congress.gov/119/plaws/publ12/PLAW-119publ12.pdf

Electronic Frontier Foundation. (2025, June). NO FAKES Act has changed — and it’s so much worse. EFF Deeplinks. Retrieved June 27, 2025, from https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2025/06/no-fakes-act-has-changed-and-its-so-much-worse

Cohen, S., & Schnapp, D. (2025, April 14). Congress reintroduces the NO FAKES Act with broader industry support. AI Law and Policy. Retrieved June 27, 2025, from https://www.ailawandpolicy.com/2025/04/congress-reintroduces-the-no-fakes-act-with-broader-industry-support/

Lorenz, T. (2025, May). The Take It Down Act is a free speech killer [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved June 27, 2025, from https://youtu.be/FVvea5CcsFc